3

City & Village Tours: 0208 692 1133

entered the Dark Ages - a term that has long fallen out of

favour with historians. One thing is for sure, this

Game

of Thrones

millennium, all pelt-clad Goths & Vandals,

wasn’t a great time for being famous. Alaric the Visigoth?

Otto the Great? It warms up a bit with Charlemagne and

Alfred the Great is maybe as famous as it gets. This was

a period when the most efficient way for news to travel

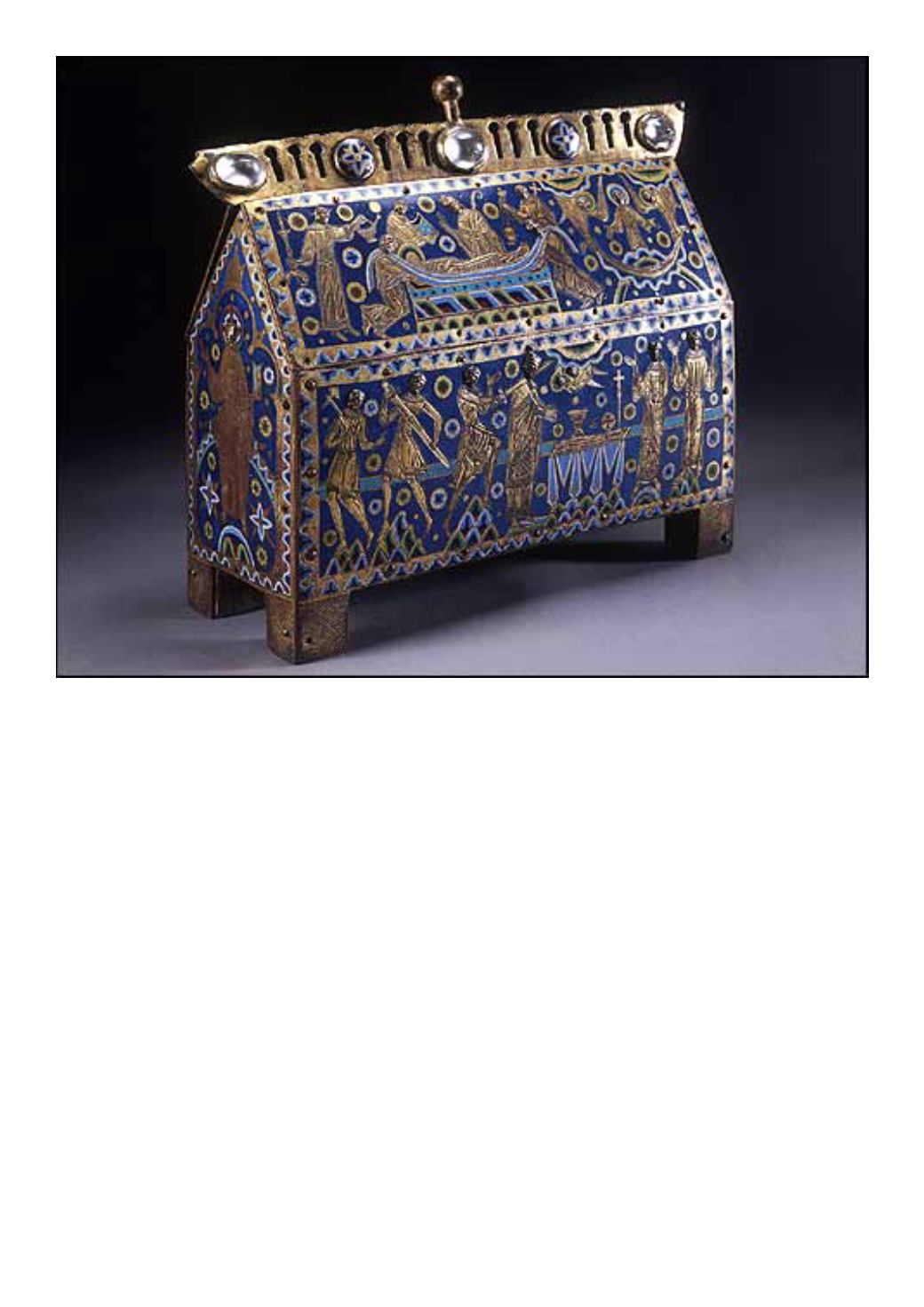

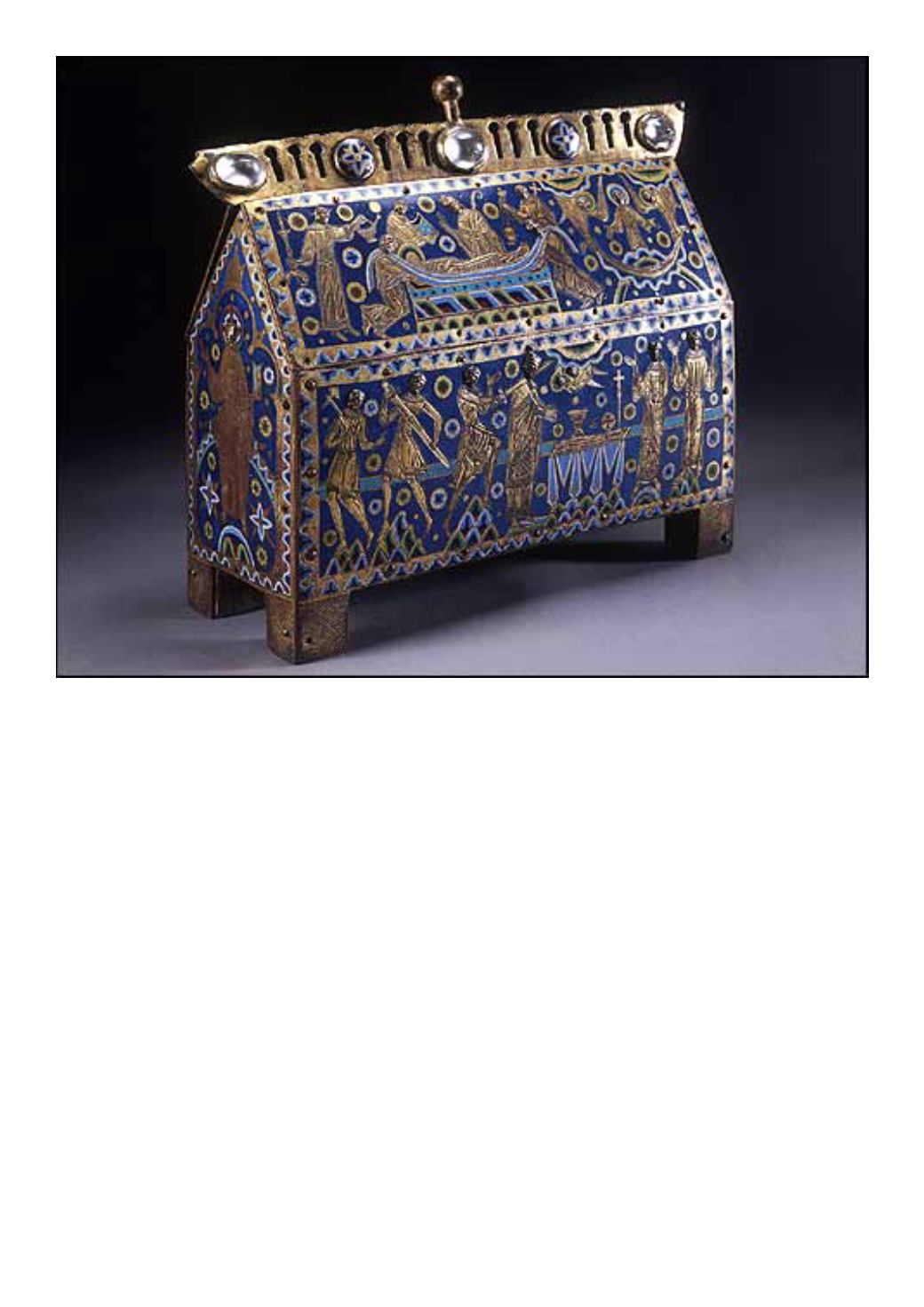

was via the clergy and so it was that in the 12th century

news of the martyrdom of Thomas a Beckett travelled

across Europe by word of mouth and in letters between

a literate clergy. The very lucrative industry of

pilgrimage was promoted with a flurry of hand copied

pamphlets and souveniers to take home with both Beckett

and Canterbury Cathedral becoming star attractions.

In the late 1300s Geoffrey Chaucer writing about fame

spoke of

blowing your own trumpet

. Chaucer achieved

a measure of fame in his lifetime but as he wrote his best

known work

The Canterbury Tales

about fifty years

before the invention of the printing press and at a time

when still very few people could yet read and write his

fame was limited. In the 1500s Shakespeare became

famous in his own lifetime but although printing was

now widespread he cared little about seeing his work

on the page. Unscrupulous and avaricious printers

however were quick to cash in on his fame with

plagiarised and poorly written versions of his plays often

cobbled together from being in the audience.

The point is the extent of your fame relies on the means

available to spread the word about yourself. Alexander

the Great had an empire full of subjects who could carry

the word and physically erect the statues and mint the

coins that would show his likeness to a vast number of

people. If you hadn’t got your own empire the next best

thing was a printing press - and ideally someone whose

job it was and in whose interest it was to write about you.

The Media Arrives

In 1641 Samuel Pecke, an innovative scrivener peddling

his services writing legal documents from a little stall in

Westminster Hall, began to use small type and narrow

margins to produce an eight page weekly newspaper.

In his day he was called

A bald-headed buzzard, constant

in nothing but wenching, lying and drinking

but today

we call him the father of British journalism. It would

take another century or so for the transport infrastructure

to improve significantly enough for publications to

become national rather than parochial. This would be

necessary for the first real revolution in the fame game.

One hundred and twenty five years after Sam Pecke the

Scrivener cranked his newsheets out on a similar scale

to a 1960s school secretary with a trusty Gestetner in the

alcove Kitty Fisher would ride the crest of the first wave

of mass media publishing with all the verve of a modern

celebrity. Kitty would manipulate the press with staged