5

City & Village Tours: 0845 812 5000

and two Jewish East Enders died. The last bomb of that

first raid fell on Stratford. From that night until the end

of the war Germany would mount fifty-two Zeppelin

bombing raids on the United Kingdom. Not all of the

airships that took part in the raids were Zeppelins but

the name very soon became the

Hoover

of airships.

Brave Men

They were called

Baby Killers

by the British press but

the Zeppelin crews were undoubtedly brave men fighting

loyally and fearlessly for their country. Flying at 10,000

feet the temperature fell as low as minus 30°C so the

German crews were clad in fur overcoats on top of leather

overalls on top of thick serge uniforms on top of thick

woollen underwear. Scarves, goggles, leather helmets

and gloves completed the weather proofing and thus

encumbered the men had to climb wooden step ladders

and, dizzy from the thin air at high altitudes, they had to

pass between gondolas by crawling along narrow catwalks

that ran along the keel. Many men were lost simply by

falling overboard.

Fortified on vacuum flasks of strong coffee with

provisions of bread, sausages, chocolate and tinned stew,

that heated itself luke-warm when the tin was opened,

and armed only with paper maps, torches and hand held

compasses the raiders were entirely at the mercy of the

weather and were very often blown miles off course.

Relying on steering by dead reckoning over the sea, fog

and even heavy cloud could wreck a mission and one

lightning strike could spell disaster and death. To jump

or to burn was the nightmare question that faced every

Zeppelin crewman: parachutes were rarely carried.

Zeppelins absorbed rain adding extra weight that forced

them lower – potentially within range of anti-aircraft fire

from the ground. If ice froze on the propellers sharp shards

thrown back with terrific force might puncture the airship.

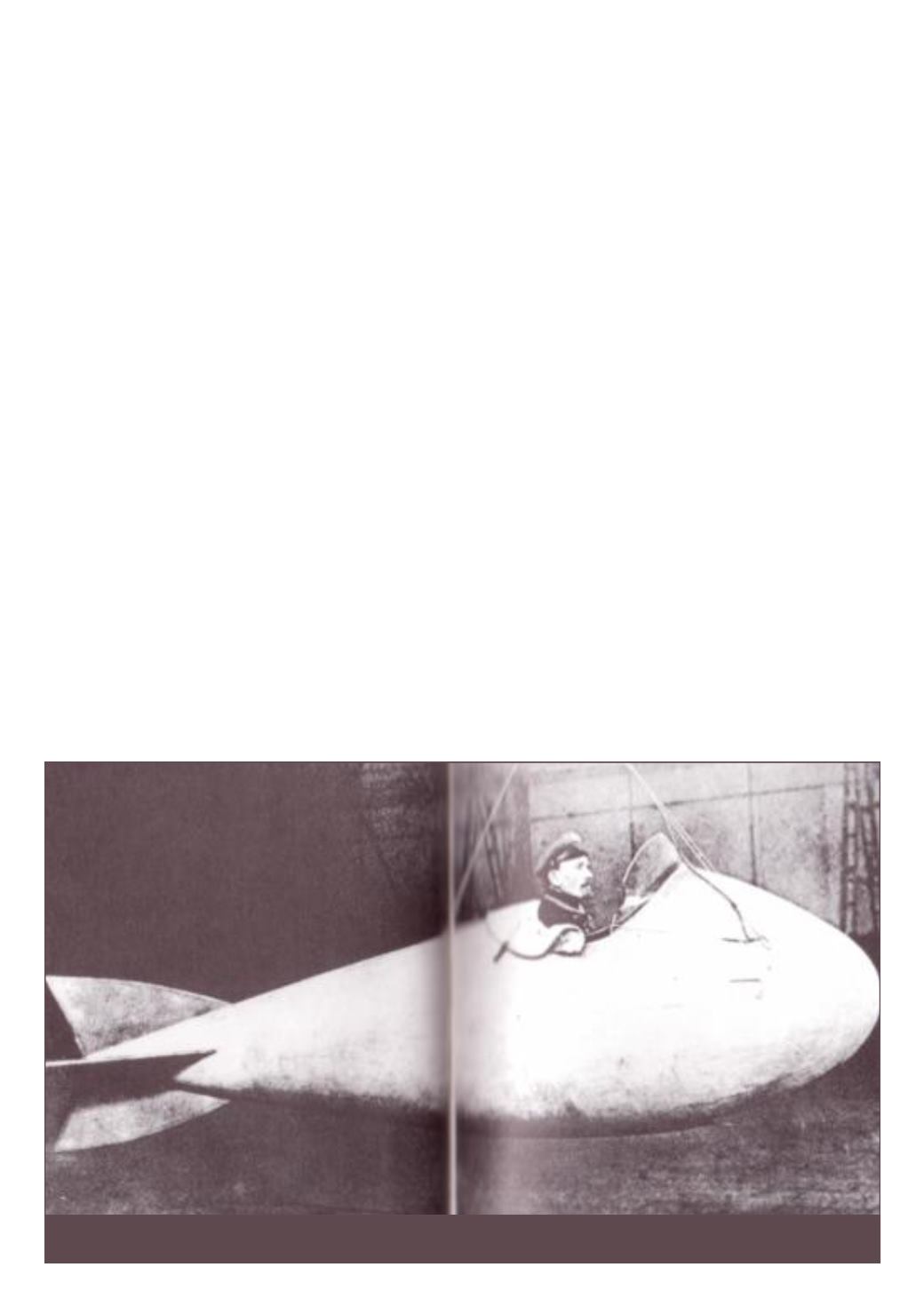

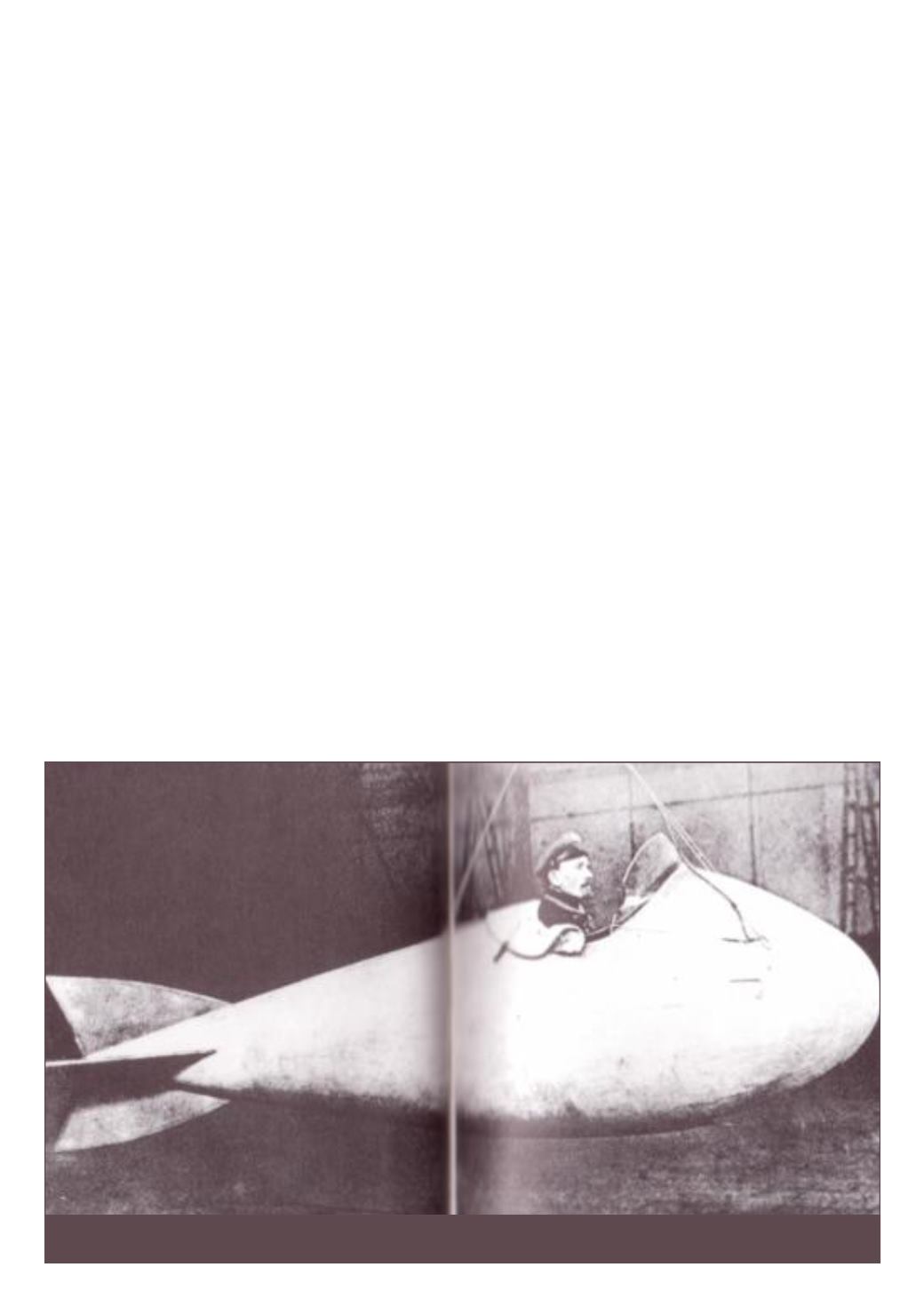

men lowered in the cloud cars first used in March 1915. If

caught in cloud the captain could throttle back the engine

and lower a steel cable on the end of which a crewman sat

in a plywood tub shaped like a cartoon bomb to dangle up

to 1000 feet below the airship and deliver

Bernie-the-Bolt

left a bit, right a bit instructions back to the airship by

telephone. There’s one in the Imperial War Museum.

Fishing for Zeppelins

At the beginning of the war the weather was by far

our biggest weapon against the airships, pretty much

everything else in our arsenal was hopelessly ineffective.

The Lewis Gun could fire a 50-100 round burst of

machine gunfire but against an airship made up of many

independent cells the worst damage would be a slow

puncture. The Woolwich Arsenal developed a flaming

bullet but it was too temperamental to be used in a

machine gun having a tendency to explode so many of

Churchill’s fleet of aircraft were armed with single-shot,

breech loading Martini-Henry cavalry carbines that had

last been fired in anger during the Zulu Wars. Obviously

built to last three Martini-Henry rifles were seized from

Taliban fighters by US Marines in Afghanistan in 2011.

Even if the pilot could hold his fragile craft steady enough

and free both hands in order to fire these

sawn-off rifles

it

was unlikely that they’d reach sufficient altitude to take

aim let alone climb high enough to fly above the Zeppelins

to drop bombs as the aircraft available in 1914 and 1915

might take 50 minutes to reach 10,000 feet. This limitation

rendered ineffective the only other weapons available early

in the war including the Rankin Darts – 1IB bombs with a

sharp steel nose to pierce the skin of the Zeppelin and four

pivoting tail vanes to snag on the envelope and fire the

detonator. A weapon developed at the Army Factory at

Farnborough, but thankfully never issued to the Royal

The terrifying Cloud Car that would be trailed up to 1000 yards beneath the Zeppelin